There are a couple of misconceptions about how often the Bridge is painted. Some say once every seven years, others say from end to end each year. The truth is that the Bridge is painted continuously. Painting the Bridge is an ongoing task and a primary maintenance job. The paint applied to the Bridge’s steel protects it from the high salt content in the air which can cause the steel to corrode or rust.

As the Bridge was built, it was painted International Orange, with a lead primer and a lead-based topcoat. Painting of the various Bridge structures then continued into the next several years. Spot painting of the steel continued in various areas of the span on an as needed basis until 1968. For more information about the International Orange color, visit the Color & Art Deco Styling page.

By 1968, advancing corrosion sparked a program to remove the original lead based paint (primer and topcoat) and replace it with an inorganic zinc silicate primer and vinyl topcoats. This process was completed in 1995. Note that in 1990, the topcoat was changed from a vinyl to an acrylic emulsion to meet air quality (Volatile Organic Compounds or VOC) requirements.

Painting continues today and is based on priorities which are determined by inspections that assist in determining where the corrosion of the steel is advancing. In 2012, there were two major paint projects along with touch-up projects - repainting the two main cables and the painting of the north approach viaduct structures.

Painting & Maintaining the Bridge FAQs

A:

The Golden Gate Bridge has always been painted orange vermilion, deemed "International Orange." Rejecting carbon black and steel gray, Consulting Architect Irving Morrow selected the distinctive orange color because it blends well with the span's natural setting as it is a warm color consistent with the warm colors of the land masses in the setting as distinct from the cool colors of the sky and sea. It also provides enhanced visibility for passing ships. If the U.S. Navy had its way, the Bridge might have been painted black and yellow stripes to assure even greater visibility for passing ships.

back to top

A:

Many people ask about the formula for the Bridge’s unique International Orange paint color. Paint stores can mix it with the following information:

CMYK colors are: C= Cyan: 0%, M =Magenta: 69%, Y =Yellow: 100%, K = Black: 6%.

The closest existing color codes to the International Orange color formula are PMS 173 (CYMK = 0%, 80%, 94%, 1%), PMS 174 (CYMK 8%, 85%, 100%, 34%) and Pantone 180 (CYMK 19.4%, 77.9%, 79.6% 3.6%).

Currently, the paint is supplied by Sherwin Williams and is made to match the Bridge International Orange color formula. The closest off-the-shelf paint color that Sherwin Williams has available is "Fireweed" (color code SW 6328).

back to top

A:

Actually, the term Golden Gate refers to the Golden Gate Strait which is the entrance to the San Francisco Bay from the Pacific Ocean. The strait is approximately three-miles long by one-mile wide with currents ranging from 4.5 to 7.5 knots. It is generally accepted that the strait was named "Chrysopylae" or Golden Gate by Army Captain John C. Fremont, circa 1846. It is said it reminded him of a harbor in Istanbul named Chrysoceras or Golden Horn.

back to top

A:

No. Painting the Golden Gate Bridge is an ongoing task and the primary maintenance job. The paint protects the Bridge from the high salt content in the air which rusts and corrodes the steel components.

back to top

A:

Many misconceptions exist about how often the Bridge is painted. Some say once every seven years, others say from end-to-end each year. Actually, the Bridge was painted when it was originally built. Until 1965, only touch up was required. In 1965, advancing corrosion sparked a program to remove the original lead-based paint (which was 68% red lead paste in a linseed oil carrier). The removal continued to 1995. In 1965, the original paint was replaced with an inorganic zinc silicate primer and acrylic emulsion topcoat. In the 1980s, this paint system was replaced by a water-borne inorganic zinc primer and an acrylic topcoat. The Bridge will continue to require routine touch up painting on an on-going basis.

Many misconceptions exist about how often the Bridge is painted. Some say once every seven years, others say from end-to-end each year. Actually, the Bridge was painted when it was originally built. Until 1965, only touch up was required. In 1965, advancing corrosion sparked a program to remove the original lead-based paint (which was 68% red lead paste in a linseed oil carrier). The removal continued to 1995. In 1965, the original paint was replaced with an inorganic zinc silicate primer and acrylic emulsion topcoat. In the 1980s, this paint system was replaced by a water-borne inorganic zinc primer and an acrylic topcoat. The Bridge will continue to require routine touch up painting on an on-going basis.

back to top

A:

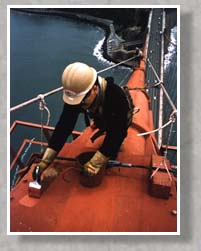

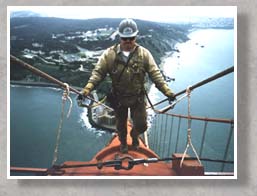

Currently, a revered and rugged group of of 13 ironworkers and 3 pusher ironworkers along with and 28 painters, 5 painter laborers, and a chief bridge painter battle wind, sea air and fog, often suspended high above the Gate, to repair corroding steel. Ironworkers replace corroding steel and rivets with high-strength steel bolts, make small fabrications for use on the Bridge, and assist painters with their rigging. Ironworkers also remove plates and bars to provide access for painters to the interiors of the columns and chords that make up the Bridge. Painters prepare all Bridge surfaces and repaint all corroded areas.

Currently, a revered and rugged group of of 13 ironworkers and 3 pusher ironworkers along with and 28 painters, 5 painter laborers, and a chief bridge painter battle wind, sea air and fog, often suspended high above the Gate, to repair corroding steel. Ironworkers replace corroding steel and rivets with high-strength steel bolts, make small fabrications for use on the Bridge, and assist painters with their rigging. Ironworkers also remove plates and bars to provide access for painters to the interiors of the columns and chords that make up the Bridge. Painters prepare all Bridge surfaces and repaint all corroded areas.

back to top

A:

Since 1970, as various construction projects and painting projects occur across the Bridge, the original rivets are being replaced with ASTM A-325 high-strength bolts of equal diameter. In the early 1970s, corroded rivets were replaced with ASTM A-325 high-strength bolts dipped in organic zinc rich primer prior to installation. When galvanized ASTM A-325 bolts became available in the mid-1970s, corroded rivets have been replaced with galvanized high-strength bolts.

When installing high strength galvanized bolts, they have to be pre-tensioned a certain amount so they “clamp” the connection together rather than “pin it” together. Using a predetermined torque value can result in being either over or under the required pre-tension depending on the roughness of the contact surfaces of the turning elements. Using the “turn of the nut” method sidesteps the potential over or under pre-tensioning problem, but it varies depending on the length of the bolt. So, what is normally done is that workers establish the “turn of the nut” rotation and torque value based on the specific length of a lot of bolts under clean conditions. They then tighten it by “turn of the nut” method and check it with a torque wrench that is calibrated first to the specific lot of bolts being installed.

back to top

Painting During and After Original Construction

From the Fiscal Year 1938/1939 Annual Report:

“The largest item in the maintenance budget is for painting of the structural steel. The past fiscal year, the sum of $112,431.84 was expended for painting of the Bridge structures. This amount was divided as follows: Labor, $86,589.13; brushes, tools, etc., $5,430.67; paint, $20,412.64.

“The exposure to salt-laden fog is more severe at the Golden Gate than any other bridge in the Bay Area. Not only is the fog extremely active in attacking the paint film but it also limits the hours when painting can be done. Over thirty percent of the working hours during the last fiscal year could not be utilized for outside painting because of weather conditions.

“The condition of the paint on the steelwork was so critical at the time of the Bridge opening that an acceleration of the original painting program was necessary. This situation arose because two conditions were not thoroughly understood at the time the original estimate of operating costs was made, namely (1) the severity of exposure and (2) the importance of special treatment of the steel surfaces prior to erection. On steel structures erected subsequently to the Golden Gate Bridge, steel surfaces have been treated by sandblasting or flame cleaning prior to erection. Failure to use either of these special treatments has added greatly to the cost of maintenance painting. The six months’ delay in the construction of the Bridge also contributes to this additional cost since, at the time the Bridge opened, the main towers, or over forty percent of the tonnage had already an exposure of one year. Prior to completion of the Bridge, contractors and the District found it necessary to expend over $130,000 for paint maintenance on the towers and main span.

“Immediately after the steel contractor completed his work in December 1937, the District organized a small crew of painters who had previous experience on the Bridge while working for the contractors. The crew starts at the bases of the towers where the rust had attacked the rivet heads and surfaces. The steel was thoroughly cleaned and a hot application of coal tar paint made at these points.

“The majority of paint failures has been caused by the loosening of mill scale. Rusting progresses under the loosened mill scale so that soon much of the surface is involved and it is necessary to remove most of the paint and thoroughly clean the metal surfaces. After trying the available methods of cleaning, the use of pneumatic chipping hammers with specially-made studite-tipped tools was adopted as being the most economical. After the rust and scale has been removed by chipping hammers, a flame dehydration torch is passed over the metal. The flame effectively dries out the moisture between the plates and around rivet heads and also removes all remaining traces of scale leaving a warm, dry surface to receive the priming coat. This surface is thoroughly wire-brushed and immediately primed while still warm and dry.”